Lately, Christopher has been tireless like the Energizer Bunny. He crawls, stands, does squats, climbs, and sings all day with his operatic mother. He has even started to walk with hints of running here and there. I could confidently tell you that, like most young-uns, his work capacity is bar none.

Work Capacity

Work in the field of physics is defined by this formula: Work = Force x Displacement. In other words, work is done when you move an object. Work capacity, then, can be understood as the ability to combine muscular endurance and strength and being able to do work without getting too fatigued. A metcon in Crossfit, for example, would be a form of work capacity.

Work in the field of physics is defined by this formula: Work = Force x Displacement. In other words, work is done when you move an object. Work capacity, then, can be understood as the ability to combine muscular endurance and strength and being able to do work without getting too fatigued. A metcon in Crossfit, for example, would be a form of work capacity.

Work capacity applies to all facets of life but it is especially critical in sports. In the sport of squash, for example–I mention squash because many of my athletes are squash players–its players must exhibit high-power output and high-level of endurance during a match. On its professional level, heart rate of players could run high as 180 to 190 beat/minute during a match. And because the players on average get only about 10 seconds between points, it requires tremendous amount of work capacity to be successful. As the famed Vince Lombardi of the Green Bay Packers used to say: “Fatigue makes cowards of us all.”

Training for Work Capacity

The best way to improve work capacity is to increase your training intensity. This does three things: 1) increases the body’s ability to buffer the acid produced by the muscles; 2) increases the body’s mitochondria capability–the power house of our cells; 3) strengthens the heart to increase cardiac output.

The best way to improve work capacity is to increase your training intensity. This does three things: 1) increases the body’s ability to buffer the acid produced by the muscles; 2) increases the body’s mitochondria capability–the power house of our cells; 3) strengthens the heart to increase cardiac output.

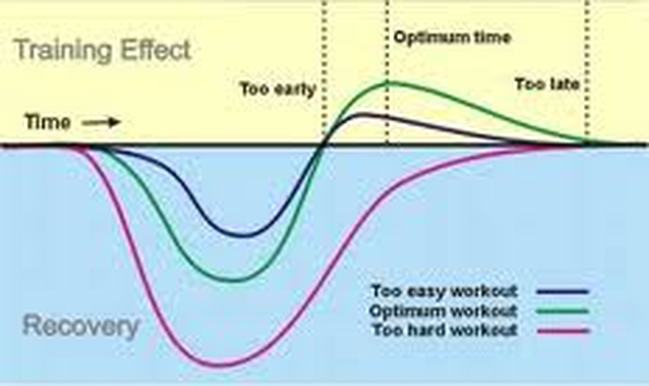

The training goal is to get the body to acclimate to a HR intensity of 85% of maximum–according to Kate, at this HR range, you will sweat through your clothes and need lie down on the floor afterwards. You can calculate your HR numbers here. The important fact is that any training higher than 85% is not better and is counter productive. So, if I take an athlete to his max exhaustion, it takes away from his ability to recovery and adapt to the training stimulus. This type of training in the long-run will lead to over-training and mental burning out–this also will increase the possibility of injury as well.

Thus, in order to prevent burnout and over-training, not only is it important to keep the training intensity at tops 85% of max HR but institute a de-load week into the training program. The goal of de-load is to back-off every 4-6 weeks (personally, I de-load every 3 weeks because I train 5-6 days/week). Generally, a decrease to 40-50% to previous training intensity should do the trick. Remember, the critical factor is that stimulus must be followed by proper recovery, which leads to proper adaptation, and subsequently to positive training effect. In short, be sure to train hard, but be even more sure to recover adequately from each training session through rest and proper nutrition. As the famed architect Ludwig Miles van der Rohe once stated, “less is more.”

0 responses to “PL Part V: Exciting and exhiliarting world of Work capacity”